How COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials currently underway around the world may be the blueprint for future clinical trial designs

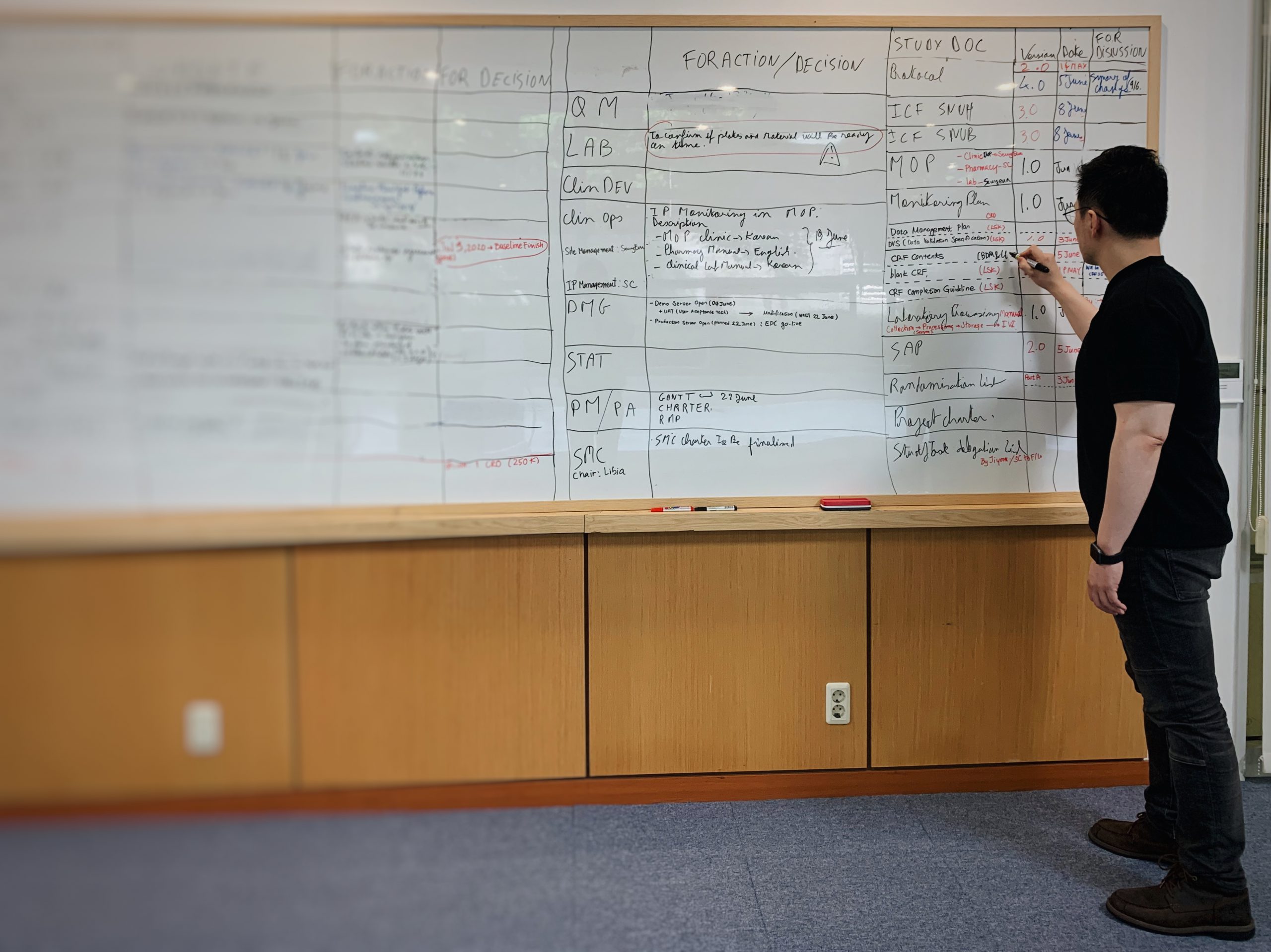

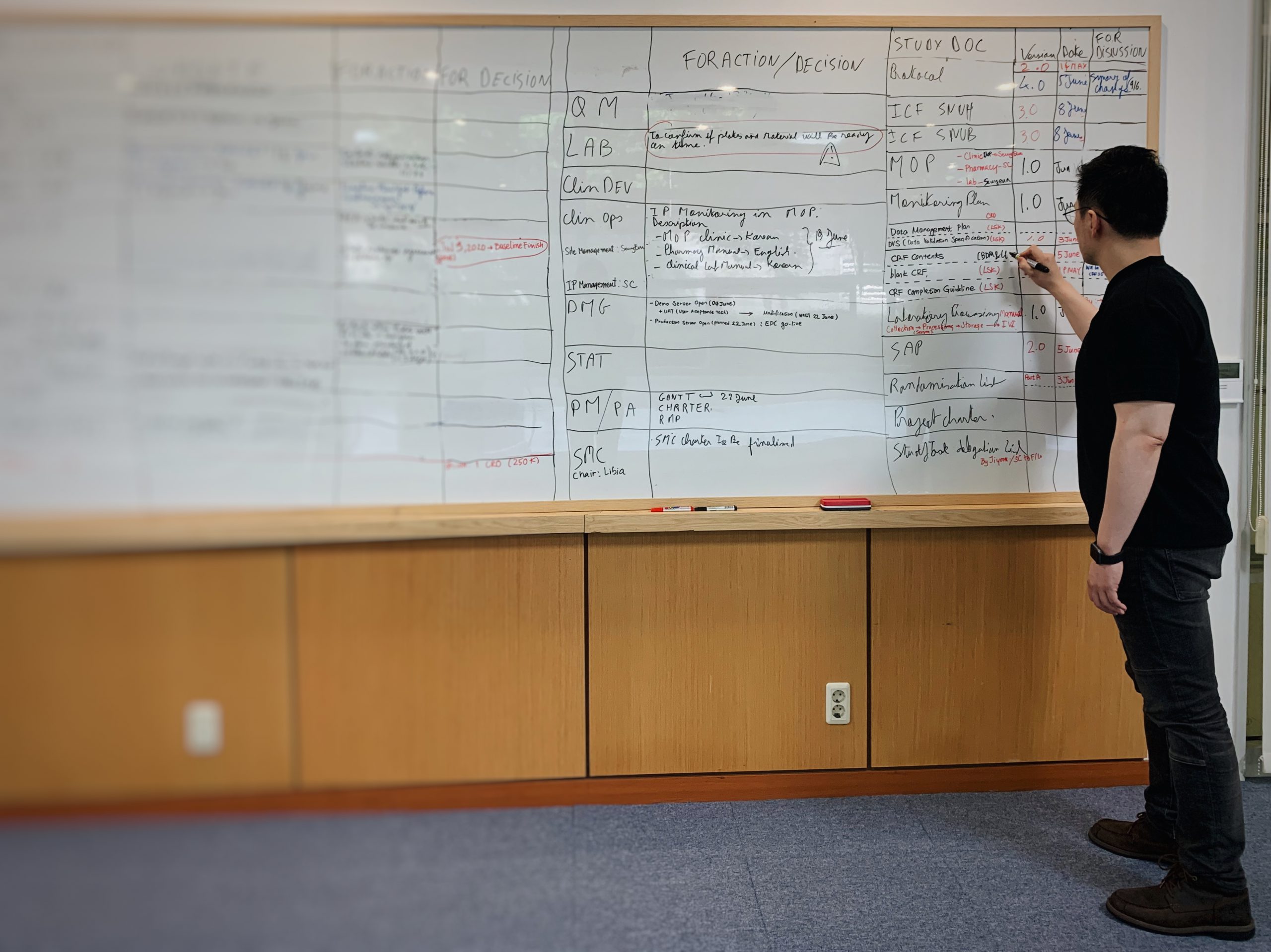

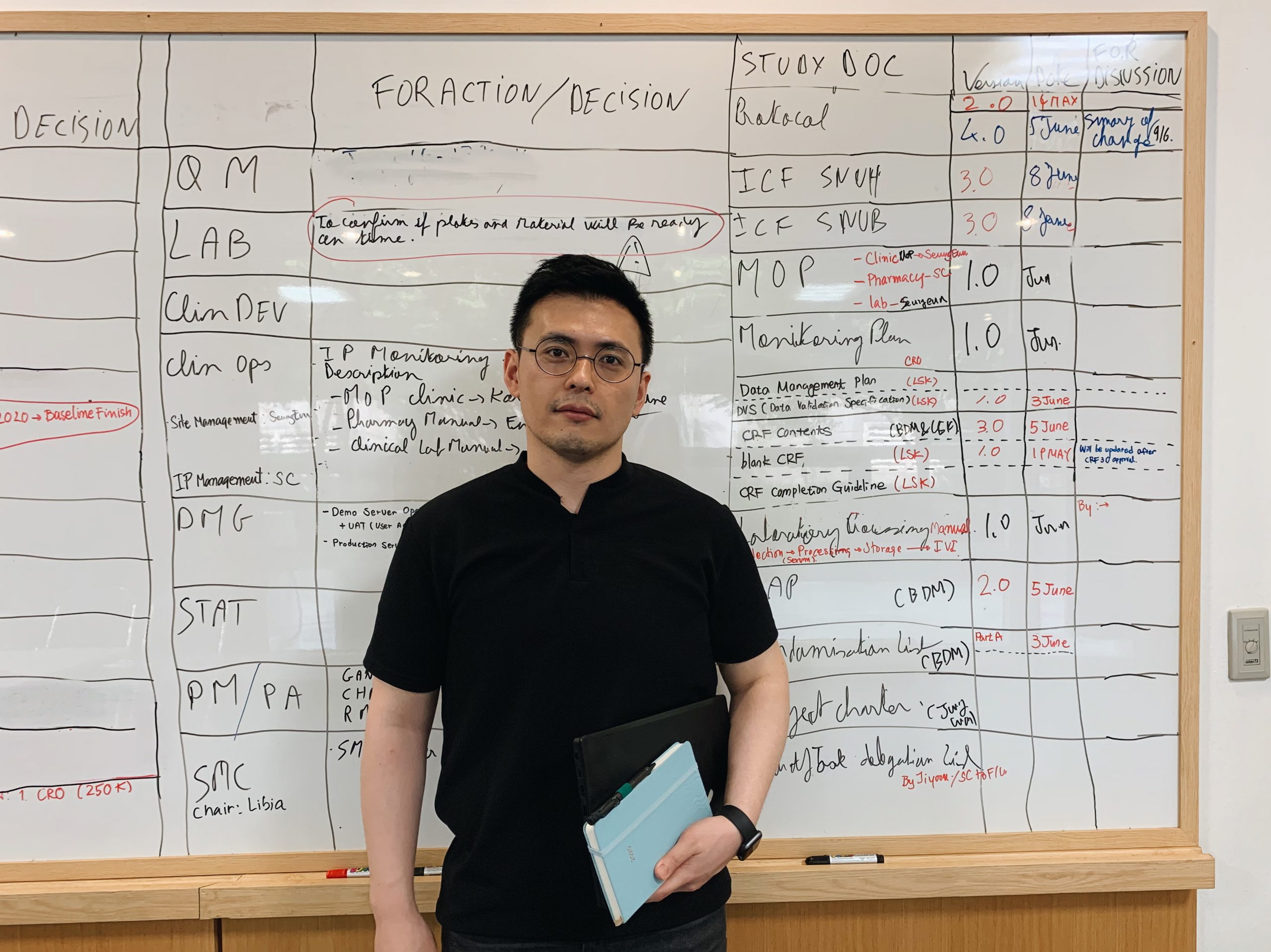

The team meets at 8:30 AM every morning for a daily “huddle.” All conversation revolves around a whiteboard filled with due dates, action items, pressing issues to address, and the names of team members in charge of them.

IVI’s COVID19-001 team regularly checks in to keep track of progress. Credit: IVI

Preparing for a clinical trial is nothing new for the members of this team, which includes experts from clinical development and operations, biostatistics and data management, quality management, and project management and administrative supports. But on April 1, 2020, the IVI COVID19-001 team kicked off a project in uncharted IVI territory: planning and executing the institute’s first vaccine clinical trial in Korea and doing so at unprecedented speed to respond to a global pandemic.

In early February, Korea was confronted with the second largest COVID-19 outbreak following China. Attention turned to the peninsula, not only for the country’s outbreak containment strategy that has since earned global praise, but also as a potential site for clinical trials for vaccine and therapeutic candidates. For where there are cases, there is an opportunity to learn about the disease and how to prevent or treat it.

Amid this on-going outbreak, IVI quickly responded by developing a concept note with INOVIO, a US-based biotech company, to apply for funding from CEPI for vaccine trials. Within a month, CEPI granted one of eight awards to INOVIO, and IVI became the sponsor for the trial of INOVIO’s DNA vaccine candidate (INO-4800) in Korea. On May 15, IVI submitted all the paperwork to Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS), and by June 2, the regulatory authority gave the green light, or, the Investigational New Drug Approval. A mere six weeks after receiving funding, IVI was set to begin Phase 1/2.

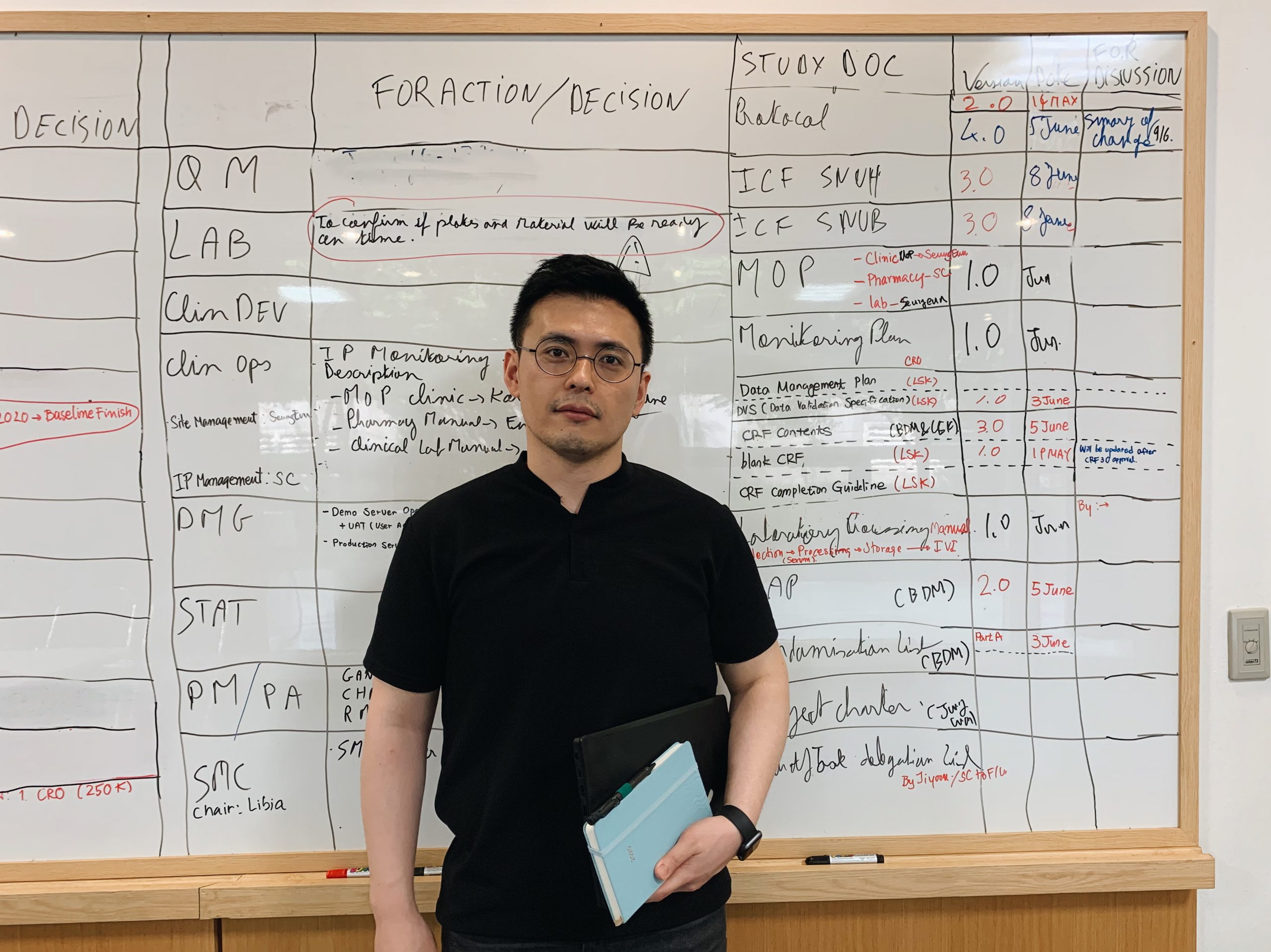

Dr. Daniel Chulwoo Rhee, Project Lead of IVI’s COVID19-001 team. Credit: IVI

Dr. Daniel Chulwoo Rhee is the Project Lead for IVI’s phase 1/2 clinical trial of INO-4800 in Korea. Prior to IVI, he worked at the US CDC in Atlanta to respond to global outbreaks of diseases like Ebola, Zika, MERS and Cholera. He’s no stranger to the urgency of responding to devastating and rapidly spreading diseases, but he, like his counterparts around the world, has been adapting to a vastly accelerated timeline.

At the moment, managing tight turnarounds and expectations are the greatest challenge, Dr Rhee says. “Agency’s ample experience and institutional knowledge in conducting clinical trials in global health settings is a major advantage, but conducting a trial is different in every country. There are local requirements you have to be aware of, as not all regulatory authorities are identical.”

IVI’s COVID19-001 project team at the Seoul National University Hospital to make official their partnership to conduct a Phase 1/2 clinical trial of INO-4800 in South Korea. Credit: IVI

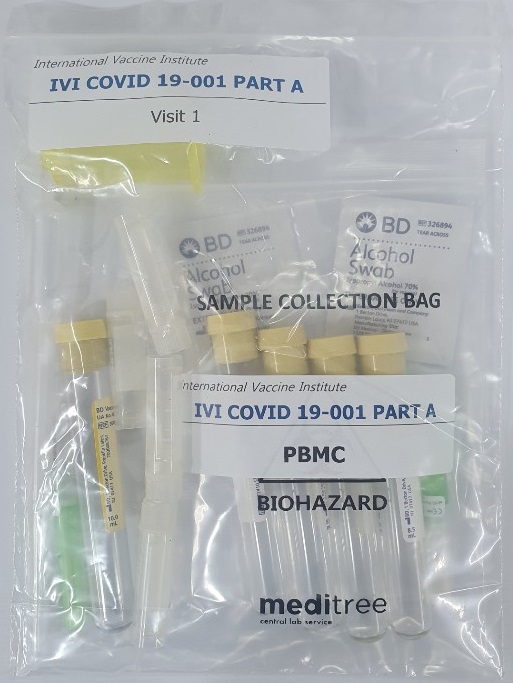

Beyond setting the urgent pace of progress, the pandemic of course presents logistical challenges at every step of clinical trial preparation. Orders for lab materials and supplies must be made, filled, and shipped at proportionate speed; however, with labs and hospitals around the world gearing up to begin their own trials, these necessities are in high demand.

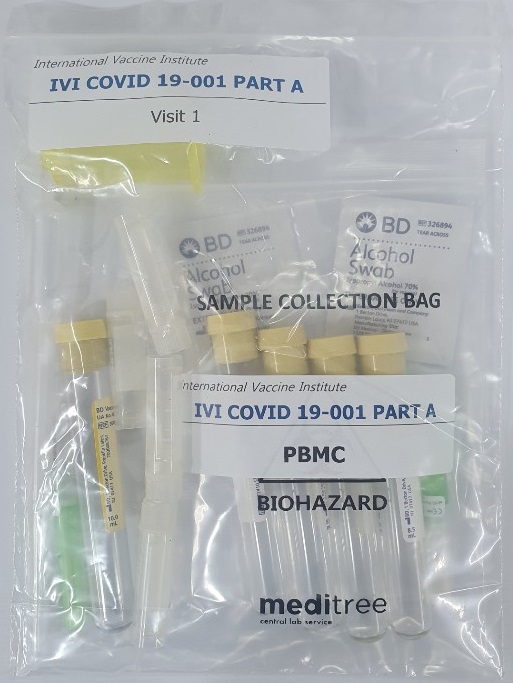

One way the IVI team has worked with a local supply partner to accommodate such logistical hurdles is to stagger production of the clinical supply “box,” which contains tubes, barcodes, cryovials, needles—all the required equipment for a highly controlled environment like a clinical trial site. While the production of these boxes may normally be completed in bulk fashion over the course of weeks, the IVI team has decided to distribute clinical supplies to trial sites in a rolling manner, sending dozens first and expecting to deliver additional supplies at regular intervals in the coming weeks as they become available.

Clinical supplies are in high demand all over the world. IVI is working with a local supply partner to produce and receive the supplies at staggered intervals. Credit: IVI

“As someone with experience in outbreak responses, working on a medical countermeasure for an emerging disease like COVID-19 is hugely exciting. The way we do clinical development right now for COVID-19 will set examples for future outbreaks.”

Dr. Rhee explains that traditionally, a clinical trial enrolls tens of people in Phase 1, hundreds of people in Phase 2, and thousands of people in Phase 3. That’s the usual equation, and it would be unorthodox to deviate from the ethical and regulatory pathways. “But now,” he points out, “there’s a trial in the UK doing a Phase I/II with more than a thousand participants.”

He admits that he could not have predicted that clinical trials could be conducted so quickly and efficiently with the same level of ethical and regulatory scrutiny, and credits the global haste to both the urgency of the moment and the painful lessons learned from previous public health events of international concern, such as the 2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Shortened timelines to conduct epidemiological studies and clinical trial phases during outbreaks have become a modern blueprint around the world, Dr. Rhee says:

“This is only possible because we have lessons learned with Ebola and Zika. Ebola was a major global health event in 2015 in West Africa, and it showed us what happens if we don’t have a mechanism in place to pull off research amidst an outbreak. By the time we were ready for vaccine clinical trials for Ebola, the outbreak was nearly over.”

Dr. Rhee believes that clinical trials will continue to advance in this direction for emerging pathogens. As an outbreak specialist, he’s hopeful that increased efficiency and collaboration among countries, industry and science, and greater incentive to invest in vaccine R&D will help combat future epidemics. “We can’t be late again,” he said.