by Jerome H. Kim, MD, Director General of the International Vaccine Institute

Originally published in JoongAng Ilbo (in Korean) and the Korea JoongAng Daily (in English).

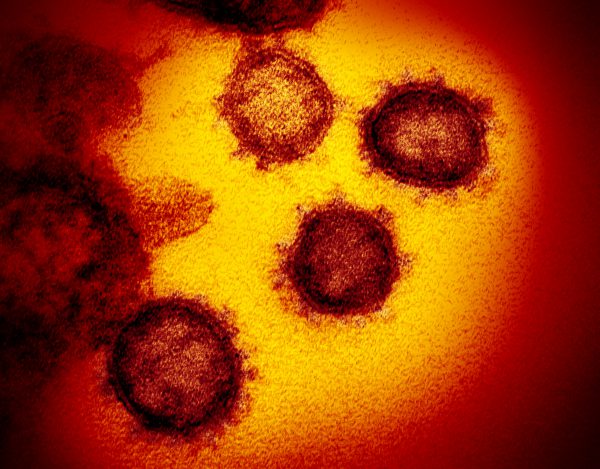

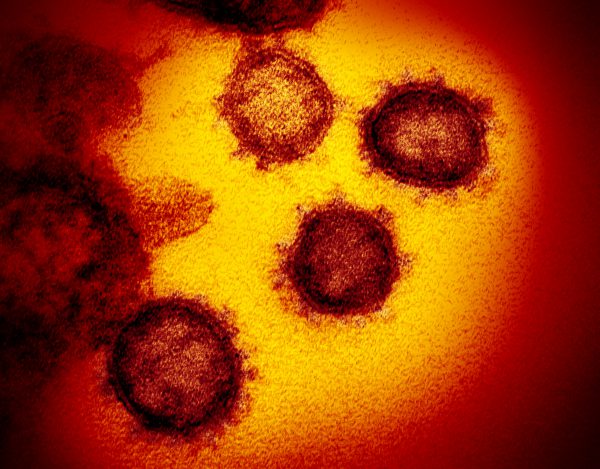

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2—also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19. isolated from a patient in the U.S., emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. Credit: NIAID-RML

80,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, and rising. 2700 deaths, and rising. The Korean government raised the alert to its highest level. However, it is still hard to see where the COVID-19 epidemic will end up. Will it abate and disappear, like the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) did in 2003? Will it revert to a pattern of occasional outbreaks in high risk populations, like the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)? Or will it adapt into the human population and will the coronavirus’s abilities to mutate and hop between mammalian species (bat, human, etc) create recurrent seasonal outbreaks with variations on the original COVID-19, as influenza does? Some have argued that it has become a “pandemic” but that word, with its potential for panic, should be used with care.

First we need to know the threat – we still don’t have complete information, but we can generalize. It is more contagious than MERS, possibly more contagious than SARS, but less deadly than either and definitely less contagious than measles. . Transmissible by droplets– so roughly a couple of meters around an infected person – and possibly by touching a surface where virus particles have been deposited by air or contact. COVID-19 enters the body through the mouth, throat, lungs, nose, or eyes.

SARS, MERS, avian flu, Ebola – the past 20 years should have taught us some lessons. With each the research community is asked – when will the vaccine be ready? When we say 5-10 years, people are disappointed. Unfortunately the funding for vaccines and new drugs goes away right after media attention wanes. It means that the next time the disease appears we are empty-handed. Vaccines and drugs take time to develop, test, manufacture and implement. These cannot be developed, as depicted on television, in the space of a single episode, but are the product of years of development — and millions of dollars. This work is done with little likelihood that the vaccine will generate billions of dollars in return on investment, and what country wants to use its money for an epidemic that may never appear again?

There is a collective solution, however, funded by countries and philanthropies to take vaccines for emerging diseases quickly from the laboratory to a stockpile so that the vaccine is available for testing or use when a new outbreak occurs. The lessons of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa led to the founding of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which has roughly 1 billion dollars in pledges from countries, organizations and philanthropies around the world. Staffed by experts in vaccine development, CEPI first aimed to develop vaccines against MERS, Lassa fever, Nipah virus, and a virus called Chikungunya. When COVID-19 emerged, CEPI was ready, and quickly provided funding to 4 groups with “rapid” technologies – one group had designed a potential vaccine within 3 hours of seeing the virus sequence. By the early summer these vaccines may be tested in humans, and if the outbreak continues some vaccines will be tested for efficacy. For process that often takes a decade, it is a persuasive argument for preparedness.

There are cogent arguments for sharing risk, in planning jointly for the contingencies that epidemic outbreaks thrust upon us. Korea and other Asian countries should join and support CEPI. Korea learned a $10 billion lesson from MERS, and it would be prudent not to have to learn that lesson again.

Read the original full article in Korean here.

And the English version as it appears in the Korea Joongang Daily here.