Omicron is dodging the immune system—but boosters show promising signs

Initial data on the new variant have experts worried about its ability to spread rapidly. But vaccine boosters still seem to be effective, as do some monoclonal antibody therapies.

Two weeks after the world first learned about the Omicron variant, scientists now agree that it spreads faster than Delta, and it seems to evade existing immunity more easily than previous variants. But whether it causes more severe illness is still up for debate.

Despite multiple travel bans, the Omicron variant has already spread to 57 countries and has now been detected in 21 U.S. states. At least for now, though, Delta remains the most prevalent variant in the world and still causes most COVID-19 deaths globally.

Omicron was first detected in South Africa, and an ongoing analysis shows that it is the most contagious variant to date in that country. By the end of November—the most recent date for which data is available—Omicron accounted for 70 percent of all South African cases; it is projected to have risen to over 90 percent by now.

At the epicenter of the Omicron outbreak is South Africa’s Gauteng Province, where daily cases of COVID-19 are doubling about every three to four days. In the town of Tshwane, active COVID-19 cases have tripled from 6,697 to 20,425 within a week. And in Gauteng, the most populous province of South Africa, one in three tests are returning positive. This positivity rate means there is high transmission in the population, and the actual number of COVID-19 cases is likely to be even higher than the officially documented number.

A virus can spread faster because it might be more transmissible or because it can evade previous immune responses.

“Some of Omicron patients are shedding a lot of virus,” says Leo Poon, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong who detected some of the first cases of Omicron outside of South Africa. Poon’s study has shown that Omicron spreads very efficiently through air, “which may be causing higher transmission.”

But the evidence is converging that the “main advantage of Omicron [over Delta] comes from immune escape,” says Tom Wenseleers, an evolutionary biologist and biostatistician at the KU Leuven University in Belgium.

Why is Omicron different from past variants?

Multiplying viruses frequently mutate because of errors in replicating their own genetic material. So with each of the hundreds of thousands of new daily infections, the virus gets that many opportunities to mutate.

“Viruses are mutation-generating machines”, says Sergei Pond, a virologist at Temple University who has shown the trends in evolution of SARS-CoV-2 lineages.

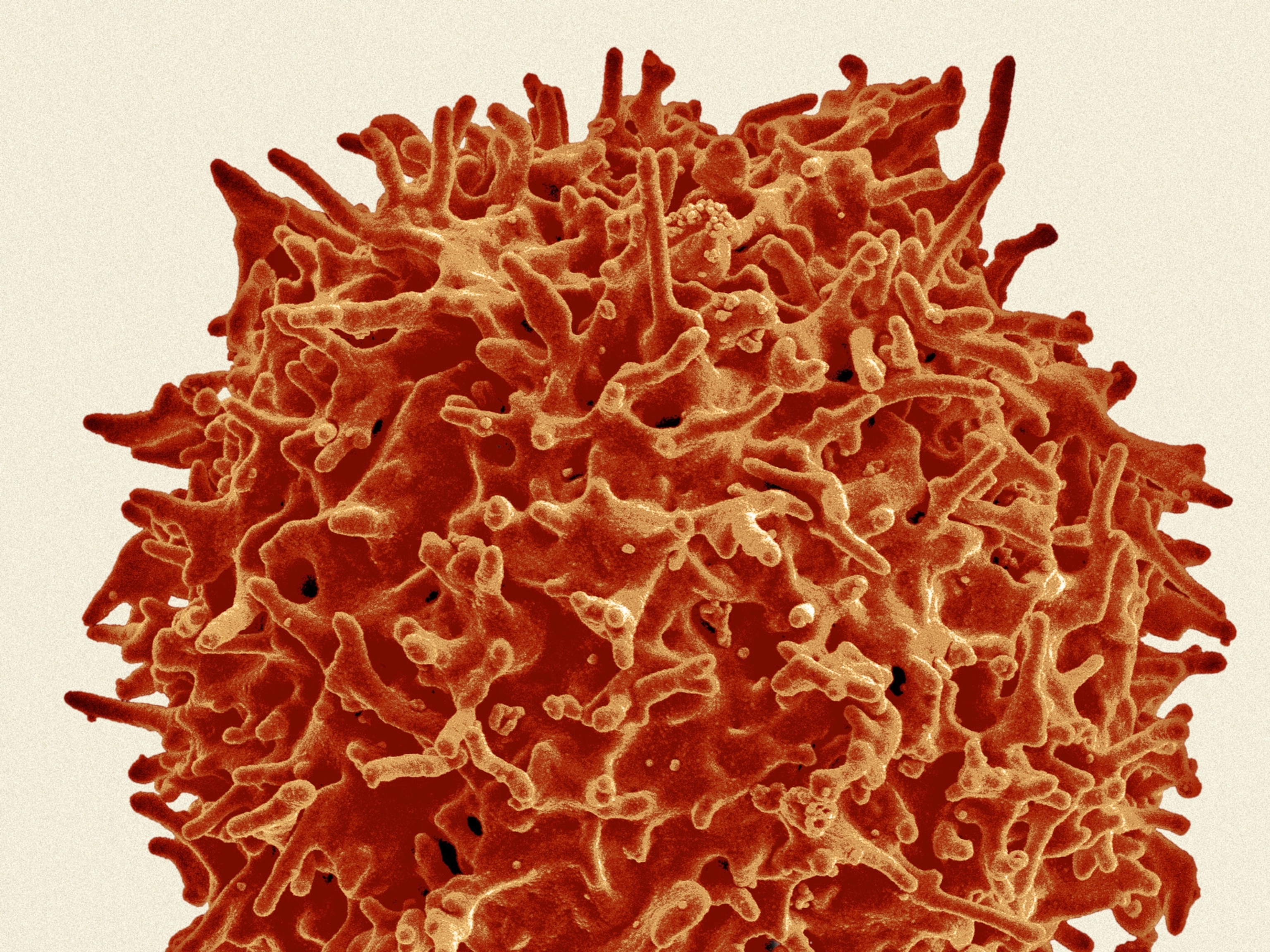

New mutations in Omicron’s spike protein are a particular cause for concern. The spike is critical for SARS-CoV-2 to infect human cells and is the main target for antibodies. Mutations there can change the appearance of the spike and make it more difficult for antibodies to recognize and bind to it, enabling the virus to evade immunity.

Omicron has undergone over 50 mutations compared to the original virus, with over 30 mutations in its spike protein.

“When you put them all together, there's so many that there's the theoretical possibility that the shape of the spike protein will be overall substantially changed,” says Herbert “Skip” Virgin, an immunologist and chief scientific officer of Vir Biotechnology, Inc., which is developing COVID-19 therapeutics.

“We don't have any direct measurements of clinical impact of Omicron yet,” says Pond, but his preliminary analysis has identified significant changes in Omicron that are likely to influence both antibody neutralization and spike function.

Can Omicron reinfect those with natural immunity?

What has researchers most concerned is that Omicron can evade existing immunity, escaping antibodies generated through natural infection.

“Omicron, as opposed to Delta, appears to reinfect people who had previously been infected,” says Jerome Kim, head of the International Vaccine Institute in Seoul, South Korea. In South Africa, Omicron seems to be reinfecting about two and a half times more people than all previous variants.

“Reinfection risk has increased markedly since the beginning of October in South Africa, and this seems to correspond with the emergence of the Omicron variant,” says Juliet Pulliam, director of the South African DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis in Stellenbosch.

Analyses of antibodies in blood samples have estimated that 60 to 70 percent of people in South Africa had already been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 before Omicron was spotted. Pulliam’s study, which is not yet peer reviewed, scoured the PCR results of 2.5 million South Africans for evidence of reinfection. Her team found that about 10 percent of all infections in November occurred in people who had previously been positively diagnosed with COVID-19 since March 2020.

“This is what one would expect if Omicron is more resistant to neutralizing antibodies,” says Theodora Hatziioannou, a virologist at the Rockefeller University in New York City.

Are vaccines still effective against Omicron?

There are reports of post-vaccinated infections occurring with Omicron in Hong Kong, Minnesota, and Norway. In Denmark, where COVID-19 surveillance is very high, Omicron accounted for 3.1 percent of all cases in the past two weeks or so. That suggests the variant can spread even when more than 80 percent of the population is fully vaccinated.

“I was actually one of the first verified Omicron cases outside of Africa,” says Maor Elad, a cardiologist at Sheba Medical Center, Israel, who caught Omicron during a visit to London for a conference despite wearing masks and having received three doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

“I had symptoms for 48 hours: fever, muscle aches, sore throat, and then I was weak, fatigued, unwell for two or three additional days. But after five days, I recovered completely,” says Elad. Even if vaccinated, he adds, you can still get infected. “Vaccine efficiency is not 100 percent.”

However, it’s too early to assess whether current vaccines are not going to be effective against this new variant.

In the study by Poon in Hong Kong, Omicron patients had been fully vaccinated with Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine five to six months before they caught the variant. And from a preliminary report from Tshwane by the South African Medical Research Council, six of the 38 adults who contracted COVID-19 as of early December were vaccinated, 24 were unvaccinated, and eight had unknown vaccination status.

It’s also not yet clear whether vaccination status can explain the larger proportion of younger patients catching Omicron in South Africa. Only about 25 percent of people under 35 in that country has received a COVID-19 vaccine, and just 33 percent of the population in Gauteng is fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

In a press release, Pfizer says that three doses of its vaccine neutralize Omicron in lab studies, while two doses may be significantly less effective. This is in line with independent but still preliminary laboratory studies that suggest Pfizer’s vaccine is less effective against Omicron relative to the ancestral virus and previous variants.

But if the company’s data holds up, booster doses of the current vaccine should still provide some immunity. And multiple vaccine-makers are now racing to modify their vaccines for Omicron specifically.

Does Omicron cause more severe disease?

It’s still too early to assess the full impact of Omicron’s effect on disease severity because it takes about two weeks from infection to development of symptoms. However, even though hospitalizations are rising rapidly in South Africa, a report documenting the first two weeks of the Omicron wave shows that deaths—which tend to rise between two and eight weeks after the start of a new COVID-19 wave—in the biggest hospital in Gauteng have not echoed the dramatic rise in cases.

According to this early report, most patients didn’t show respiratory symptoms, most were admitted to the hospital for other medical reasons, and the length of hospital stays for COVID-positive patients was 2.8 days, compared to the average of 8.5 days during past 18 months.

That could be because “Omicron is still mainly circulating among younger people. Eighty percent of the hospitalized patients in Gauteng Province are under 50,” says Wenseleers, who has modeled earlier waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Younger people typically endure milder infections than older people.

“Even now, we don't know whether Omicron could cause more severe clinical outcome or not,” says Poon. He led the team that sequenced the 2003 SARS coronavirus, established the earliest PCR test to diagnose SARS-CoV-2, and was on the international team of virologists that named the virus.

There is also no guarantee that Omicron’s impact in the U.S. and Europe—which have older populations—will be the same as in South Africa. But preliminary data as of December 8 showed that among all 337 Omicron cases detected in the European Union, symptoms were either mild or not present, and no deaths related to the new variant have been reported in member countries.

But even milder but more transmissible variants can be dangerous, according to Michael Ryan, Executive Director of the WHO Health Emergencies Program. If allowed to spread unchecked, the virus can infect greater numbers of people, who then overwhelm health systems, causing a spike in deaths. Worryingly, an analysis from the U.K. Health Security Agency suggests that the window between infection and infectiousness may be shorter for Omicron than for the Delta variant.

Will current therapies still work?

Four monoclonal antibody products are currently authorized to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 in non-hospitalized patients who are at high risk for progressing to severe disease or hospitalization.

In a study not yet peer reviewed, a monoclonal from GSK and Vir Biotechnology called Sotrovimab remained effective against a lab-made Omicron-like virus. “Sotrovimab is capable of neutralizing the Omicron variant, including all 37 of the mutations, [which makes us] very optimistic that Omicron can be dealt with therapeutically,” says Vir Biotechnology’s Virgin.

“Despite the considerable evolution of the virus with Omicron, we have evidence that effective therapeutics are available to control the pandemic,” says Davide Corti, a leading antibody researcher at Vir Biotechnology. That’s critical if Omicron causes a high percentage of cases in people who are vaccinated. Whether other therapeutic antibodies can block Omicron is currently unknown, but Virgin remains optimistic about available treatments.

“The vaccines are a remarkable accomplishment, even if they lose activity against a certain variant,” he says. “People should get vaccinated, and should they begin to develop symptoms that might be due to coronavirus, they should immediately seek medical attention, because it's not hopeless."

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct the percentage of patients in South Africa in November who had previously been positively diagnosed with COVID-19. It is 10 percent.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- Spend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the worldSpend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the world

- How nanobreweries are shaking up Portland's beer sceneHow nanobreweries are shaking up Portland's beer scene

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture